BY CYNTHIA CHOCKALINGAM, CIVIL RIGHTS UNIT INTERN AT SAN

During the summer of 2020, the height of this “modern” Black Lives Matter movement, I had a conversation with my father—sitting in a car driving through Hammond, Indiana to see what had happened to our old, predominantly black and brown community—that started out with: “Appa, I do not understand South Asians can be against Black Lives Matter. The work of Black Americans is integral to why we can even be here today.” We went on for a while brainstorming as to why so many members of our South Asian community were still not strong supporters of this movement. We only found one solution; many of us never learned what made it possible for us to be in this nation today and are uneducated on Black struggles.

Members of the South Asian community counter that Black Americans do not work as hard as us, which is why South Asians appear to be more successful and suffer less. However, this overlooks the difference in histories of migration between the two groups. Anti-Blackness in the South Asian community here in America is rooted in a lack of education and a lack of empathy. This month South Asian Network will be focusing on Black Lives Matter and Black History. Before looking at how the Black community contributed and helped our South Asian community, it is important to understand how the Black experience has been different from our own. While a fight for equality should never even have to be justified, we at South Asian Network recognize this unjust treatment and recognize that some of this hatred and racism comes from our own community. As a result, we are using our voices here in hopes that our people will be strong and whole-hearted supporters of Black communities and Black Lives Matter.

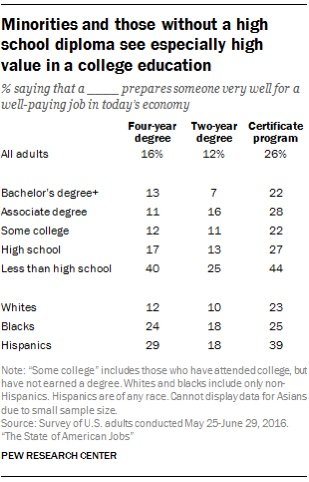

Now, we come back to why South Asians, as well as many other minorities, are not empathetic of Black people: they believe that as minorities, we all struggle alike, but unlike Black people, we are much more successful because we work harder. This in itself contains multiple misconceptions. Ultimately, we—South Asians—have not had the same history as Black Americans. The Pew Research Center explains that 69% of Asian Americans say people can just “get ahead if they are willing to work hard,” thus making them blind to the struggles of others. Privileged people tell Black people, “Get a job!” so they can be successful. Unfortunately, a disproportionate amount of Black people do not have the luxury of just getting a high paying job—not even a rich job, just one to keep their families well-supported. However, many traditional high paying jobs (traditional meaning do not require someone to take a gamble with their entire life and savings or do not need to be heavily financed with investments, like a generous donation from one’s parents) require college degrees. In fact, the SEED Foundation explains that since the Great Recession, 4.6 million jobs created have required a bachelor’s degree while only 800,000 require a high school diploma or less. The Black community recognizes the importance of a college education for a future; CNBC contextualizes that while 65% of Black adults say college is “very important,” only 44% of white adults give college that same value.

Today, college costs close to $48,510 for a private institution and $21,370 for public annually. Due to historical and present redlining, many Black people, including those who were financially well-off, were forced into poorer communities or were essentially robbed. CBS corroborates that “Black families have lost out on at least $212,000 in personal wealth over the last 40 years becaue their home was readlined.” As a result, children in these communities, many Black, go to severely understaffed and underfunded schools—some even dealing with abrupt school closures like in Gary, a town near my hometown. Built 93 years ago, Roosevelt high school in Gary could have housed 4,000 students but after white-flight that left the city hurt, there are now 4,500 students in the district all together according to American School & University Magazine. The state of this city is and its school district is depicted in a popular Vice documentary. In it, they explain Gary has come down to pretty much just 2 functioning high schools. When Black people have been pushed to communities like these, have limited educations that decrease the chances of admission into good colleges along with necessary financial aid, are subsequently unable to get competitive jobs, how can they be blamed for the hole white people and the government has put them in? While redlining has been made illegal, single-family zoning laws still keep those with less money from well-funded schools in wealthy communities.

How does this contrast with the stereotypical successful Asian? Asians had a different migration process that led us to not be catapulted into the same cycle of poverty. The Pew Research Center recounts that, “Large-scale immigration from Asia did not take off until the passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.” After which significantly more Asian immigrants came skilled and educated. They continue, “Today, recent arrivals from Asia are nearly twice as likely as those who came three decades ago to have a college degree, and many go into high-paying fields such as science, engineering, medicine and finance.” If we were to forget for a moment that this Asian view of hard work and success was highly stereotypical and generalized about ourselves, the people this generalization is based on came to this nation already educated; they were ready to work in high paying fields. As a result, they were able to move to nice communities with good schools. They have now set up their families for generations to come by putting them in a good place for their children to go to college, their children will get good jobs to fund their own children’s educations, and the cycle continues.

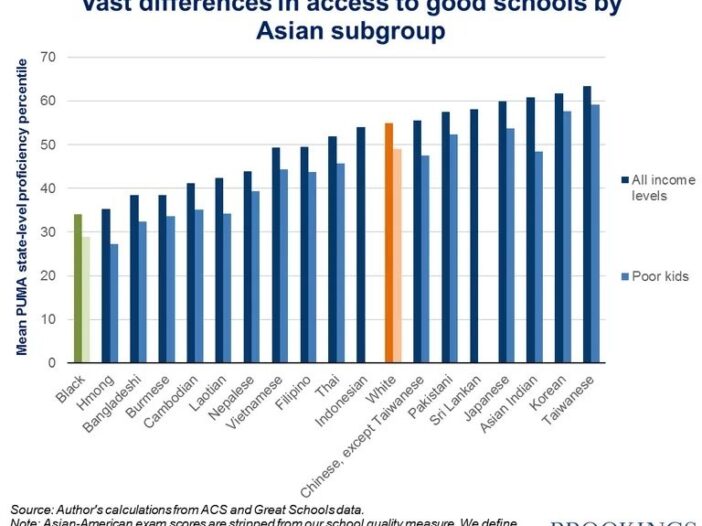

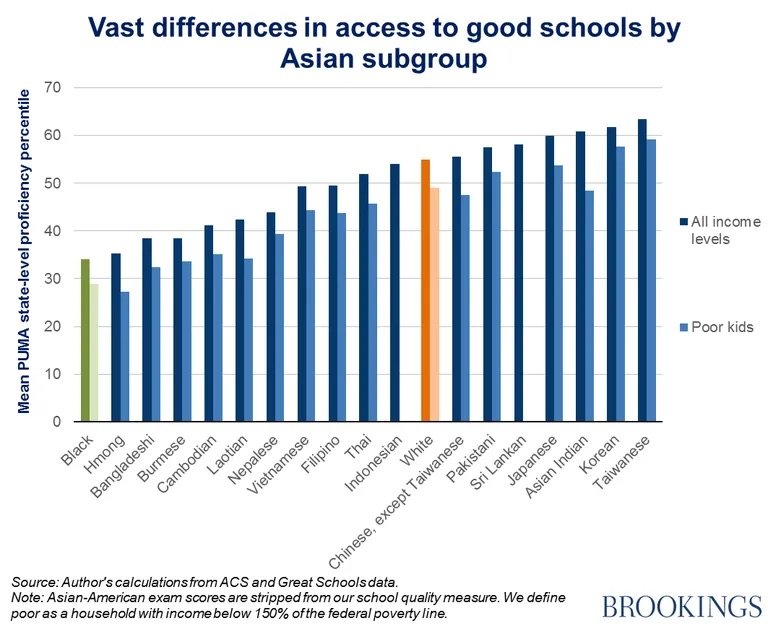

Asian success is also not determined by race, but rather income. Take Cambodians and Hmong, who have some of the highest poverty rates among Asians: they perform similarly to African American students in school. The Brookings Institute explains, “The Asian groups faring poorly are those living in areas with poorer quality schools—similar, in fact, to those in which African Americans live.”

Yet, we as South Asians and Asians continue to stereotype ourselves, as many of us here do have the privilege of coming into wealthier professions and communities. We credit our success to our race; in reality, it is due to this economic privilege. By making these generalizations, we not only undermine Black people, but also our own underprivileged, struggling South Asian communities. Rather than shaming Black people, we could be fighting as a community for better education for all. That better education is what helps all people of this nation alike to succeed in our futures.

Ultimately, South Asians and Asians views of success and their ties to race have caused harm to the Asian and Black communities. We understand now that this generation success is highly based on economic status and the opportunities provided through this status. While we recognize that stereotypes and generalizations were employed in the writing of this article, in no way are we implying that this is the experience of all. We recognize that money is not the only factor, not all Black people are poor, and not all Asians have experiences and privilege better than all Black people. What we did today was move through the generalizations that the Asian community has been using to stay prejudiced against Black people. By operating within these generalizations, we were able to attempt to dismantle the reasoning used to stay prejudiced against Black people, as they are rooted in many assumptions and hasty generalizations. While Black-Asian solidarity may not completely exist in the status quo, we must attempt to create it because the Black community is one of the reasons we as South Asians can be here today, thriving. As a result, our next article will be on the Black contributions to the South Asian community.