South Asian Network

Manju Kulkarni

Manju Kulkarni is the co-founder of nonprofit Stop AAPI Hate, which aims at targeting discrimination in the US that affects Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. She currently serves as the Executive Director at AAPI (Asian-American Pacific Islander) Equity Alliance, a coalition of organizations working for the rights of the AAPI community.

Named alongside colleagues and Stop AAPI Hate co-founders Russell Jeung and Cynthia Choi on TIME‘s ‘Icons’, Kulkarni has campaigned for racial equality for over two decades. She is a senior attorney and legal researcher based in California.

Stop AAPI Hate is founded in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic that spurred a series of racist attacks against Asians in the US, served as an “invaluable resource for the public to understand the realities of anti-Asian racism, but also a major platform for finding community-based solutions to combat hate.”

In a turbulent year, as the U.S. has seen a surge in racist, anti-Asian attacks—from terrifying assaults on senior citizens to the tragic mass shooting in Atlanta—no coalition has been more impactful in raising awareness of this violence than Stop AAPI Hate. Since its start, the organization has logged more than 9,000 anti-Asian acts of hate, harassment, discrimination and assault across the country

Stop AAPI Hate has become not only an invaluable resource for the public to understand the realities of anti-Asian racism, but also a major platform for finding community-based solutions to combat hate. And its leaders have locked arms with other BIPOC organizations to find restorative justice measures so that civil rights—for all vulnerable groups—receive the protection they deserve.

An alumna of the Boston and Duke Universities, Kulkarni has been recognized by the White House for her efforts in social work, with a focus on health for South Asian communities. She was hailed as a ‘Champion of Change’ in 2014 under then-President Barack Obama’s healthcare act.

She was the former Executive Director of the South Asian Network (SAN) organization, committed to resource access and empowerment for different racial groups.

Kulkarni, an active voice on social media, has spoken against the use of “minority” and “majority” as a descriptor for communities of people of color and is known to have said, “my identity is NOT based upon my relative percentage of the population.”

Manju received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science and a Certificate in Women’s Studies from Duke University and a Juris Doctor degree from Boston University School of Law. After graduating from college, she worked at the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Attorney General’s Office in her hometown of Montgomery, Alabama. While in law school, Manju clerked at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles, California. Manju reflects, “At the Southern Poverty Law Center, she conducted legal research to challenge district-wide voting to dilute the black vote in Alabama; at the ACLU, she sought redress for Japanese Latin Americans abducted by the U.S. government during WWII; and at MALDEF, she helped to craft legal arguments to secure in-state tuition for undocumented students. The opportunities she had at SPLC, the ACLU, and MALDEF cemented her desire to pursue public interest law and specifically to work in the realm of civil rights.”

She asserts that the choice that most defines the woman she is today is her decision to pursue public interest law. “Pursuing public interest law enabled me to continue working as a lawyer when my children were young, allowed me to work on issues about which I was passionate and offered a number of leadership opportunities not readily available to women in other parts of the legal world. In my experience, public interest law firms and non-profit organizations have generally had more reasonable work requirements than law firms, requiring only forty hours a week rather than the sixty or so expected at private firms.

Additionally, public interest firms often allowed part-time work and offered generous parental leave; law firms frowned upon reduced hours or maternity leave beyond a few weeks. For that reason, many of my female friends and colleagues at law firms left their jobs and often their careers in the law after having a child. I was fortunate to continue working as an attorney after the birth of both my children. Upon the birth of my first child, I took off three months, working full-time, but only 40 hours a week, afterward. After my second child was born, I managed to secure six months off, after which I moved to a 70% schedule, working less than 30 hours per week, 5-6 hours per day. Moreover, my time off and subsequent schedule change had no impact on my ability to advance within the organization. Within a few years, I was promoted from Staff Attorney to Senior Attorney alongside my colleagues who had worked full-time while I was working part-time. Working in the public interest realm also enabled me to work in the areas of law about which I am passionate—to advance civil rights and to work to eliminate [some of the adverse consequences of] poverty. I have been fortunate enough that my work has had impact—sometimes substantial. In one instance, a single line I strongly recommended be changed in state health care regulations allowed fifty thousand children in California to obtain health insurance for which they previously did not qualify.

Finally, the opportunities for success in public interest law were more numerous than in corporate law firms. In public interest law, I saw other women and people of color move up the ladder in ways they would have been unable to do so on the corporate side. In my first position upon law school graduation, I was able to advance very quickly within the Office of the Civil Rights Monitor, joining the management team while still in my twenties. Similarly, as Senior Attorney at the National Health Law Program (NHeLP), I was able to access numerous leadership opportunities, including invitations to speak at large conferences, draft legislation at the state level and write appellate legal briefs. One such brief, early in my career, was presented to—and ultimately persuasive in— the California Supreme Court.

Manju offers this advice to incoming Duke women: “Be confident and speak your mind. Like your male classmates, you are bright, intelligent and fully capable of meeting the challenges a Duke education will offer. You should not be intimidated by your male peers’ bravado or swagger. You should exude confidence in and out of the classroom. You have a great deal to offer your college, your community, and the world!”

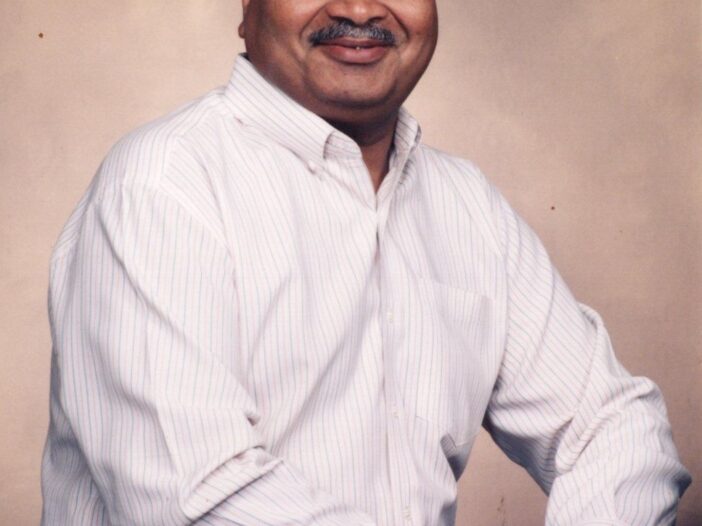

Uday Shendrikar

Uday Shendrikar is a retired Electrical Engineer. Uday received a Bachelor of Electrical Engineering (BSEE) degree from Osmania University, Hyderabad, India. After graduation, he worked in India for 3-4 years.

Uday migrated to USA in late 1966 for further studies, went to Louisiana State University (LSU), and obtained a Master of Electrical Engineering (MSEE) degree. After graduation from LSU, he started working in New Orleans, went to the evening program and obtained a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree at the University of New Orleans

Uday moved to Los Angeles area in 1973 and worked for a major Utility Company for about 25 years and started his own consulting practice thereafter. He managed and operated his consulting company for next 15 years and, in 2012, decided to call it a good time to retire.

Uday has three children, all are married and live in California. He has six grandkids and one of them will be graduating from High School by June 2022, ready to go to college in the fall 2002, waiting for notification from universities and will decide the one he likes by April 2022.